Buy-out is the ultimate goal for many private sector defined benefit pension schemes. But what is the difference between a buy-in and a buy-out and what do these scheme events mean for individual members going through divorce?

What is a buy-in?

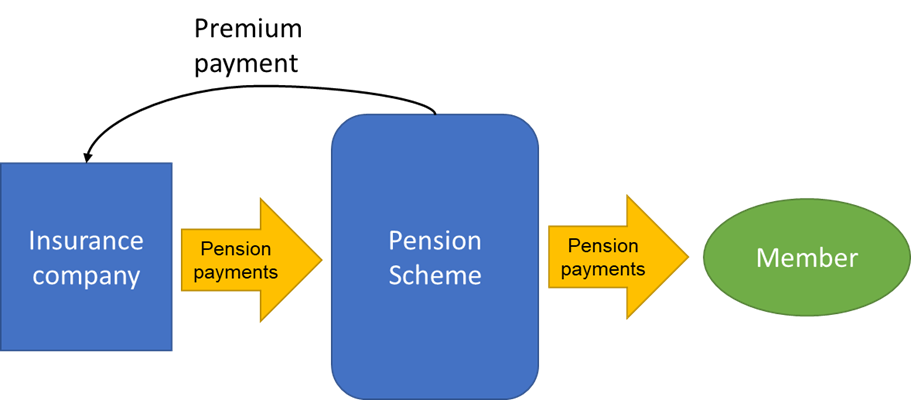

A pension scheme buy-in is an insurance contract where the scheme pays a premium to an insurance company who then takes responsibility for funding the benefits of some or all pension scheme members.

The insurer will make a regular payment to the scheme in respect of the insured benefits and the scheme continues to be responsible for paying members. For individual members there is not much change following a buy-in. There is usually no change to administration and members still get their benefits paid from the scheme. Many household name pension schemes have completed buy-ins in recent years including The Marks & Spencer Pension Scheme and The Merchant Navy Officers Pension Scheme.

Considerations for pensions on divorce

When collecting information on pensions for divorce, it might not be immediately obvious if a pension scheme is covered by a buy-in policy. However, this could still have implications for a divorce settlement. Any buy-in policies, also known as bulk annuity contracts, will be disclosed in scheme documents such as Trustee Report and Accounts however these documents do not have to be disclosed as standard under the Pensions on Divorce etc (Provision of Information) Regulations 2000.

One key area that can be impacted by a buy-in policy is the factors used by the scheme. This can include factors used when calculating cash equivalent values (CEVs), the terms for cash commutation and early or late retirement. Following a buy-in, these factors will often be set by the insurer. In theory the pension scheme trustees are still responsible for setting the factors used when calculating member benefits. However, the insurer will set the factors used when calculating the payments made to the scheme in order to fund these benefits so in order to achieve a perfect match the trustees will often adopt the insurer factors.

Insurer factors are generally linked to market conditions and reviewed more frequently than most scheme factors. There could also be a significant change to factors immediately following a buy-in transaction when insurer factors are first adopted. This is especially relevant if a pension is being shared on divorce and the basis for calculating CEVs changes before any pension sharing order is implemented. When Actuaries for Lawyers carries out data collection for private sector defined benefit schemes, one question we now ask the administrators is if the scheme has recently completed a buy-in and if so when the buy-in took place as this could have an impact on CEVs if the buy-in transaction has taken place since the most recent CEV was calculated.

It should be noted that apart from potential changes to factors, a buy-in policy does not impact the benefits that a member holds in the scheme. There is also no change to the ability to implement a pension sharing or attachment order.

What is a buy-out?

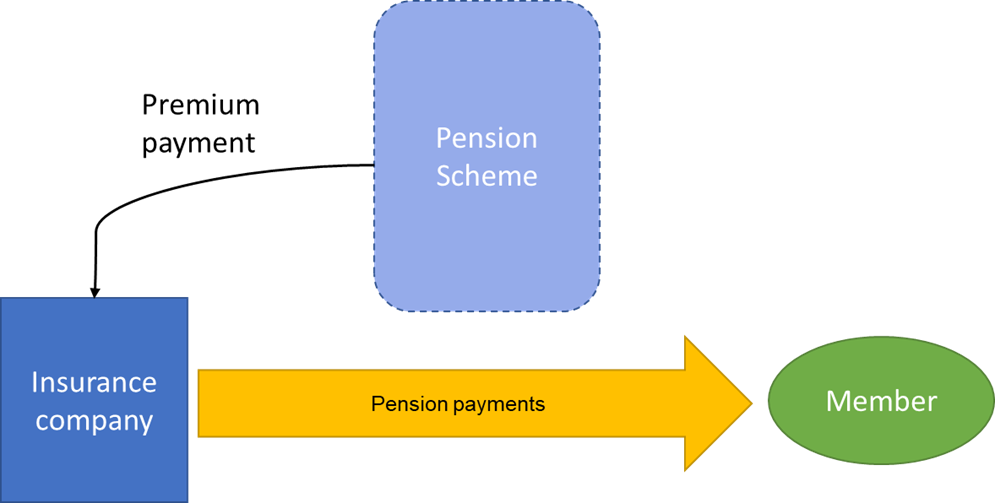

A pension scheme buy-out often follows a buy-in where a premium has been paid to the insurer who is then responsible for funding the relevant member benefits. The next step that turns this into a buy-out is that the insurer takes over responsibility for paying the members.

The insurer and scheme will go through a process to agree the final data and benefits and the insurer will then issue individual policies to the members. This means that the link to the original scheme is broken, the scheme can wind up and the insurer takes charge of administration.

For an individual member this means that their scheme benefits are replaced with an insurance policy promising to pay identical (or almost identical) benefits. Buy-outs are becoming increasingly common, whether this is for the entire benefits in the scheme or in some cases just for a group of members such as pensioners or members of a particular benefit or employer section. Household name pension schemes that have completed full or partial buy-outs of benefits in recent years include The Rolls-Royce UK Pension Fund, The Asda Group Pension Scheme and The Old British Steel Pension Scheme.

Considerations for pensions on divorce

Following a buy-out any information collected for divorce purposes will need to be requested from the insurer as the scheme is no longer responsible for administration.

Many of the considerations outlined above for a buy-in also applies following a buy-out. This includes factors which will be set by the insurer unless they were specified in the policy. Benefit security is also high and there is no longer any risk of benefits being reduced following a transfer to the Pensions Protection Fund (PPF).

The individual annuity policy with an insurer which now forms the basis for the member’s pension benefits, can be shared on divorce in the same way as other pensions. It should however now be remembered that the name of the pension arrangement in Section C on Form P1 in the Pension Sharing Annex must now be the name of the insurer and the policy number of new policy rather than just writing in the name of the former pension scheme in which the individual was a member.

Impact of adopting insurer factors

The factors used by different private sector pension schemes can vary significantly. Therefore, the impact of moving from scheme factors to insurer factors will be different for every scheme.

When it comes to CEV calculations schemes are required to be at least equal to the best estimate of the expected cost of providing the member’s benefits in the scheme. As a result, these calculations tend to be based on market conditions at the calculation date and linked to the scheme’s investment strategy. This is similar to the approach taken by insurers when calculating CEVs. This means that the difference between a CEV calculated by the scheme and an insurer will be related to the expected investment returns based on the scheme’s assets before the buy-in and the insurer’s assets after the buy-in. Depending on the different investment strategies CEVs could increase or decrease after adopting insurer factors.

Example: A member with a deferred pension of £5,000 p.a. might have a CEV of £300,000 calculated using Scheme factors based on a very low risk investment strategy immediately before buy-in. The CEV for the same benefit might be £250,000 calculated using cost neutral insurer factors, based on balanced insurer investment strategy. Note that this is an example only and in practice CEVs could increase or decrease following a buy-in. This does however indicate the importance of considering requesting a new CEV be provided, even when the previous CEV is less than 12 months old, where you become aware that a member’s pension benefits have been subject to a buy-out since the previous CEV was calculated.

The impact of changing factors can often be more significant for cash commutation (that is the process of giving up pension income to generate a higher lump sum at the point of retirement). This is because when it comes to the commutation factors used by a private sector defined benefit scheme (such as a final salary scheme) there is no legal requirement to offer members fair value. Clearly this will vary between different schemes but for many schemes these factors are updated only once every three years and tend to be low compared to the value of pension given up for a cash lump sum. Insurers on the other hand are required to offer customers fair value which means that in many cases the commutation terms can be significantly more generous than those offered by schemes.

Example: The maximum tax-free cash available for a member age 65 with a pension of £10,000 p.a. on retirement could be £50,000 using Scheme factors, leaving a residual pension of £7,500 p.a.. After adopting insurer factors the maximum cash available could increase to £54,500 with a £8,200 p.a. residual pension.

Overall, the impact of adopting insurer factors will be different for every scheme. The impact for pensions on divorce also varies depending on the approach taken to pensions sharing. For example, a change to the CEV will be significant if a pension sharing order is considered for that particular pension and cash commutation factors might be important if calculations include equalisation of retirement lump sums.

In summary, whilst buy-outs and buy-ins might not impact on all cases, this topic does underline the importance of instructing a pension expert when dealing with pensions settlements involving private sector defined benefit pension schemes with CEVs in excess of £100,000.

Disclaimer – The views expressed here are the views of the writer only and do not necessarily represent the view of Actuaries for Lawyers. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this post, it is important to always check the benefit rules with the schemes before making any financial decisions based upon these. Actuaries for Lawyers cannot be held responsible for any losses incurred as a result of relying upon information contained in the blog section of our website as these do not constitute advice or act as a substitute for providing individual advice in relation to the specifics of a particular case.