The purpose of this blog is to point out one aspect of the changes taking place for most Public Sector Schemes from 1 October 2023 and as a result of that, what action may be needed.

In general the calculations and results within reports may be invalidated over time due to various factors such as large changes to CEVs. These large changes to the CEVs could be due to things like large salary increases, extra accrual of benefit, the taking of benefits on retirement as well as other reasons. But in addition to these reasons why a CEV may change, a further potential cause has now been added as a result of the regulations coming into force on 1 October 2023 in respect of the Public Sector Pensions Remedy (consequent to the McCloud ruling).

Generalised summary of what to look out for

Action may be required where all of the following conditions apply:

- A Pensions on Divorce report has been completed, but a Pension Sharing Order (PSO) has not been implemented.

- A Public Sector pension is involved; so a pension from employment with one or more of the NHS, civil service, teachers, police, armed forces and fire and rescue service. The judiciary has been excluded from this list, because this issue does not arise. Local Government workers have not been included because their scheme has different conditions.

- The scheme member was an active member of the scheme immediately prior to 1 April 2012 and has some service in the same employment between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2022

- The intention is to implement a PSO on that public sector pension.

- When the report was produced, there must have been two sections to that public sector pension (being the 2015 Scheme section and a pre-2015 Scheme section). The sections are actually referred to as separate schemes. The PSO may only be being applied to one section of that scheme, but the overall pension from both sections together must have accrual of benefit in between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2022 (inclusive).

- The report was based on Cash Equivalent Values (CEVs) which were produced before 1 October 2023.

- A further CEV has been requested after 1 October 2023 but before the PSO has been implemented.

Action required

The parties will need to consider re-visiting the report to assess whether the results are still reliable/valid.

Reasoning

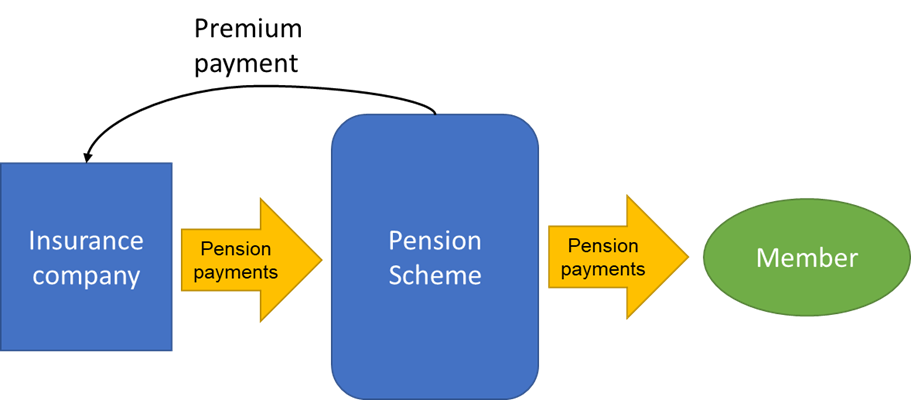

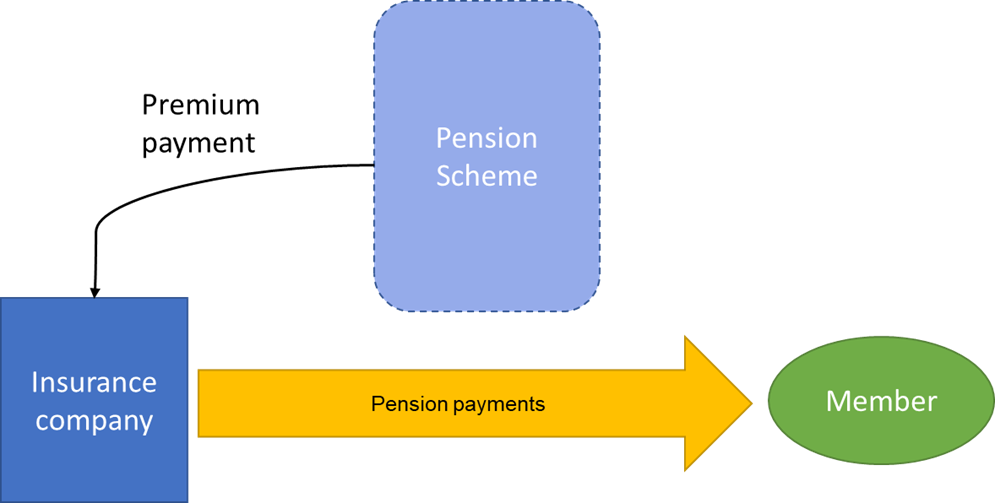

Any agreed pension share may not work as intended, and could lead to a materially different outcome, because the CEV of the underlying pension in each section may have significantly changed. This change is due to a movement of the benefit accrual for the 2015/2022 period from the 2015 Scheme section to the Pre-2015 Scheme section from 1 October 2023.

I illustrate here a very simplified hypothetical example to indicate what may be happening.

A Pensions on Divorce report has been provided with calculations effective as at 31 July 2023 with a PSO indicated of 50% of the Pre- 2015 pension based on the following CEV values

- Pre-2015 Scheme section – CEV = £50,000

- 2015 Scheme section – CEV = £100,000 (£70,000 of this is in respect of the 2015/2022 accrual period)

So the intended share is 50% of £50,000 equalling £25,000 pension credit CEV

The pension scheme member is wondering whether the CEVs may be out of date and so obtains revised CEVs with an effective date of 1 November 2023, which are provided as follows

- Pre-2015 Scheme section – CEV = £130,000 (£80,000 of this is in respect of the 2015/2022 accrual period)

- 2015 Scheme section – CEV = £30,000

If a 50% PSO is implemented on the Pre-2015 pension as at say 15 November 2023 then the pension credit CEV would now be based on the new CEVs, and so would become £65,000 (50% of £130,000), and effectively £40,000 higher than intended.

The cause of the unintended consequence in this example is that, based on the draft legislation published to date regarding Public Sector Pensions Remedy (McCloud), the methodology for calculating Pension Credit and Pension Debit amounts on the application of a Pension Sharing Order (PSO) differs depending upon whether the latest CEV (provided for divorce purposes prior to that Pension Sharing Order being sent to the Pension Scheme) is dated before or after 1 October 2023.

For divorce purposes only, if the latest CEV requested is dated before 1 October 2023, then the PSO would be based on assuming the 2015/2022 accrual had NOT moved to the Pre-2015 Scheme section, and so the pension credit CEV in the above example at 15 November 2023 would still be £25,000.

But if a CEV is requested after 1 October 2023 (or was requested before but is dated after 1 October 2023) then the PSO would be based on the actual re-allocated position of the 2015/2022 accrual into the Pre-2015 Scheme section, and the pension credit CEV would be £65,000 in the example above.

Hence, as a result of the pension scheme member requesting and being provided with a CEV dated after 1 October 2023, the PSO is implemented on a higher CEV of his Pre-2015 Scheme benefits and results in providing his ex-spouse with a greater amount of pension credit than was intended (£65,000 compared to £25,000).

A preventative action to avoid this particular issue could be to ensure that no CEV is requested for these pensions after 30 September 2023 where agreement and financial settlement terms have been negotiated on CEVs issued prior to this date. An undertaking by the pension scheme member to this effect may be considered necessary.

For more details on this public sector pensions remedy (McCloud) and some of the implications of this on pensions on divorce settlements, the position statement on Actuaries for Lawyers website provides further information on this topic (link below)

Disclaimer – The views expressed here are the views of the writer only and do not necessarily represent the view of Actuaries for Lawyers. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this post, it is important to always check the benefit rules with the schemes before making any financial decisions based upon these. Actuaries for Lawyers cannot be held responsible for any losses incurred as a result of relying upon information contained in the blog section of our website as these do not constitute advice or act as a substitute for providing individual advice in relation to the specifics of a particular case.