An important area of concern when dividing up pension rights fairly for divorce settlement purposes has been the large recent changes in inflation, with the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) nearing its highest levels for almost 30 years (according to recent ONS figures). At the same time interest rates have increased significantly over a short period of time with the Bank of England official Bank Rate increasing from a low of 0.1% in December 2021 to 1.25% in June 2022. This can affect pensions settlement in many different ways given the impact on future revaluation rates, pension valuations, and annuity rates. As a consequence of this, there are a number of issues that are worthy of consideration by pensions on divorce practitioners.

Settlements involving Public Sector Pensions

Depending upon how you look at it, some may argue that public sector pension CEVs are less affected by inflation than other pensions encountered in a divorce settlement. The main reason for this is that the Cash Equivalent Values (CEVs) of public sector pensions used in pension sharing are calculated by a factor-based method using valuation factors published by the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD) which are only reviewed infrequently. The majority of the factors currently in use were issued in 2018/19 and use a “real” valuation interest rate, that is “after” inflation, to place a value on future inflation linked pension income streams. The current valuation rate of interest is CPI + 2.4%, that is a “real” rate of 2.4% per annum and this has remained unchanged since 2018. This means that if you are calculating the CEV of an inflation linked public sector pension income of £10,000 per annum, the calculation would remain unchanged at present, irrespective of what future inflation might be.

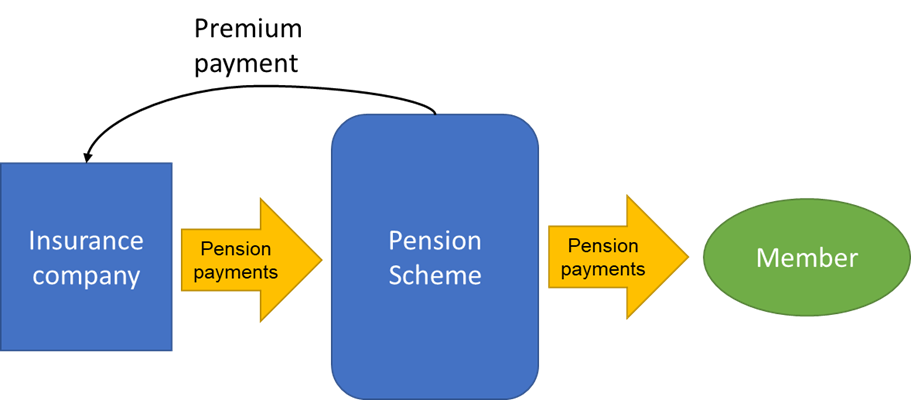

It should however be remembered that public sector pensions receive inflationary revaluation in April each year, so if CPI inflation indexation is 10% in April 2023, the pension income would increase from £10,000 to £11,000 at that point in time and this would cause the CEV to increase by 10% at that instant. When it comes to pension sharing however, the majority of public sector pensions only offer an internal share to an ex-spouse (requiring the ex-spouse to become a member of the scheme in their own right). The internal share terms are calculated by similar GAD valuation factors used to calculate CEVs and noting that an internal share calculation is like a CEV calculation but in reverse (an ex-spouse pension income is generated from a CEV credit rather than a CEV being calculated from a member’s pension income) then it is no surprise that the required pension share percentage to equalise pension incomes is unchanged, however both parties will have more valuable benefits post share than had inflation not spiked upwards, as the high rate of CPI inflation means that the actual amount of both their pension income benefits will now be higher from 2023 onwards when the next pension increase is added.

The above points are in generality, and so may not be applicable in all situations for example if the Public Sector pension is not being shared then the current holder of this pension is expected to have a significant increase next April that is not reflected in the current benefit or the current CEV. Another example could be where a pension credit is received just before next April (so in March 2023), then the pension credit member would not benefit from the April 2023 increase.

The cushioning of public sector pensions against being adversely impacted by inflation changes is not repeated in quite the same way for other types of pension arrangements as is considered below.

Defined contribution pensions

Although defined contribution pensions (those for which a fund of money is built up, which can be drawn upon in retirement or used to purchase an annuity in retirement) are the most obviously affected by changing market conditions, this can also make them the simplest to deal with. As the value of such a pension is generally based upon the value of the underlying assets in which the pension is invested, this means that the value of a defined contribution pension may significantly change when market conditions change. The simple point to remember with these, therefore, is to ensure that the CEV to be used is up-to-date (although in the interest of practicality, this can usually be considered to be within a few months of the date of any pension share being implemented noting that any material changes due to additional contributions being made or large drawdown payments being taken should always be considered when agreeing final settlement terms).

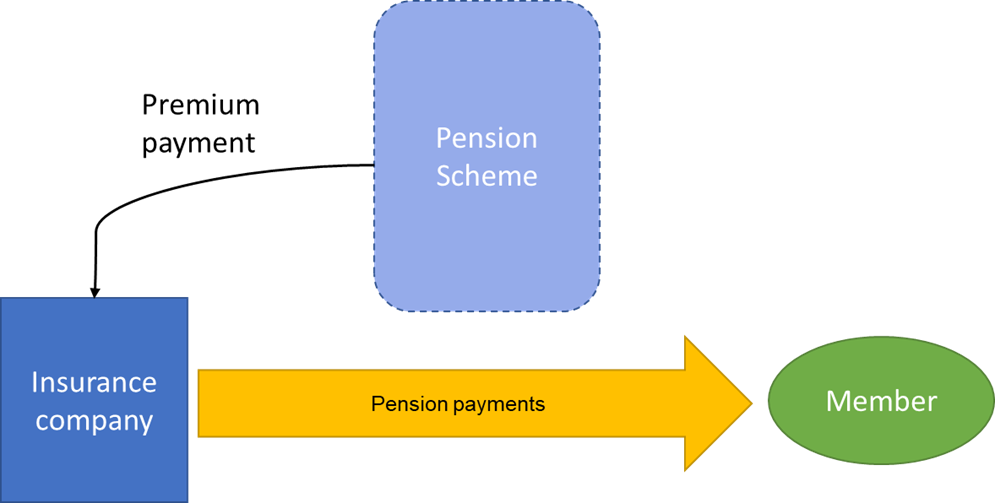

Another potential issue with market movements and defined contribution pensions lies in annuity rates, which the Pensions Advisory Group recommends should usually be considered when assessing the likely lifetime income available from a defined contribution pension arrangement. High interest rates makes UK Government Bonds cheaper to purchase and the falling prices of these have seen yields correspondingly shooting up in recent months. As insurance companies selling annuity business can now buy UK Government Bonds much more cheaply to back up their commitments to pay long term lifetime incomes, they are able to offer much more attractive terms to those seeking to buy such annuities. This is good news for those with defined contribution pensions (assuming that valuations of these pension funds have not fallen) as it means that lifetime incomes can now be secured much more cheaply than was the case a few months ago. In recent cases worked on by Actuaries for Lawyers, some annuity rates for annuities with a fixed escalation rate have improved by as much as 10-20% over the last few months, and so the expected annual income available from a pension fund when purchasing an annuity has similarly increased.

Private sector defined benefit pensions

The pension benefits paid out by defined benefit pension arrangements (such as the Railways Pension Scheme, Barclays Pension Scheme, BAE Systems Pension Scheme etc) are also affected by changes in pension revaluation rates before retirement and pension increases in payment as the scheme rules usually require that these benefits are linked to future rates of inflation in some way. In particular, the future pension income available when the pension comes into payment might increase significantly when the pension is revalued between leaving service and retirement.

One key area of difference however between private sector defined benefit pensions and public sector pensions however, is the very different method used for calculating CEVs. When private sector defined benefit pension CEVs are calculated, the scheme actuary is obliged to have some regard to future market conditions when making recommendations to the trustees of the scheme as to actuarial assumptions to use when placing a present value on the future pension income available to a scheme member. The assumptions used will be dependent on the investment strategy adopted by that particular scheme which in turn depends on a number of factors, such as the funding position and maturity of the scheme. The general principle used when calculating a CEV is to estimate the amount of money needed at the calculation date to pay the future pension benefits due to be paid to the member when they fall due. These assumptions are required to match the changes in market conditions. For example, on a recent case Actuaries for Lawyers saw a pension scheme provide a CEV in mid-2020 of around £800,000 which dropped to a more recent CEV of around £700,000 mainly due to a change in the Scheme Actuary’s assumptions of future market conditions (in this case, the most significant such condition is likely to be the assumption of future investment return).

This change in CEV means that the pension credit available to an ex-spouse following the implementation of a pension share may change materially if market conditions experience significant change. This may mean that on cases where a significant portion of the parties’ pension rights (which may be subject to a pension share) are held in a private sector defined benefit pension scheme, it might be prudent to obtain an up to date CEV if there has been a material change in the yields on medium dated UK Government bonds since the previous CEV was calculated, even if the latest CEV is less than 12 months old and there may even be a fee charged to obtain an up to date value. This is the position we are in at present as in the last few months, there have been considerable movements in the financial markets due to factors such as the significantly increasing price of energy, the war in Ukraine and consequential significant increases in CPI and RPI measures of price inflation over the past 12 months.

These issues as well as other factors have caused the yield of 20 year Government bonds to increase to a high of around 2.5% per annum at the beginning of June 2022. Whilst this may all appear quite technical, what is important here is the implication of the above on the calculation of CEVs. As CEVs are effectively placing a discounted present value on the pension income stream from the member’s normal retirement age until their eventual date of death, the higher the yield on Government bonds, the higher the discount used when placing a present value on future cashflows arising from their pension and consequently the lower the CEV would be expected to be.

When it comes to pension sharing calculations, there will undoubtedly be overlap between some of the observations highlighted above. Hence the reduction in a private sector CEV being subject to an external pension share may result in a higher pension share percentage being required to equalise pension incomes, however this may be countered to an extent by the better annuity rates now available to the ex-spouse reducing the required pension share.

Which of the above factors may dominate may be difficult to predict and will vary based upon the circumstances of the case which is being considered. The issues highlighted here underline the importance of obtaining expert advice from a pensions on divorce expert so that the possibility of unexpected consequences occurring following a pension share can minimised.

Disclaimer – The views expressed here are the views of the writer only and do not necessarily represent the view of Actuaries for Lawyers. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this post, it is important to always check the benefit rules with the schemes before making any financial decisions based upon these. Actuaries for Lawyers cannot be held responsible for any losses incurred as a result of relying upon information contained in the blog section of our website as these do not constitute advice or act as a substitute for providing individual advice in relation to the specifics of a particular case.